Projects

Lab research focuses on social media as a source of research questions and a source of data. No other technology has changed everyday lives as profoundly and rapidly as social media. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Tiktok now connect billions of people within online spaces to exchange ideas and information, work, socialize, date, entertain themselves and even fight wars. These massive, global interconnections promote liberty, openness and the free exchange of ideas. However, due to their low barrier to entry and global reach, social platforms have become a target for social manipulation by malicious actors who aim to spread misinformation, inflame culture wars, and create polarization. My research attempts to reduce these harms and increase the benefits of interconnectedness through the synthesis of social networks and AI.

Collective Psychology on Social Media

Social media connects people at an emotional level, allowing them to share their own feelings and to react to the feelings of others at an unprecedented scale and speed. Emotional connection can be a force for good, knitting people within communities that provide a shared group identity and help make sense of a chaotic world. But, it can also erode wellbeing through negative social comparisons or by trapping people within toxic echo chambers that harm mental health. Online emotions can also amplify affective polarization by exposing people to the opinions of their ideological foes, which can rapidly entrench political divides, and allow malicious actors to manipulate beliefs at scale through coordinated influence campaigns. We are mapping collective emotional dynamics at a global scale to understand the complex interplay between emotions, identity and beliefs.

Representative publications

- Lerman, K., Feldman, D., He, Z., & Rao, A. (2024). Affective polarization and dynamics of information spread in online networks. npj Complexity, 1(1), 8.

- Nettasinghe, B., Percus, A. G., & Lerman, K. (2024). Dynamics of Affective Polarization: From Consensus to Partisan Divides. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.16940.

- Lerman, K., Karnati, A., Zhou, S., Chen, S., Kumar, S., He, Z., ... & Horn, A. (2023). Radicalized by Thinness: Using a Model of Radicalization to Understand Pro-Anorexia Communities on Twitter. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11316.

- Burghardt, K., Rao, A., Chochlakis, G., Sabyasachee, B., Guo, S., He, Z., ... & Lerman, K. (2024). Socio-linguistic characteristics of coordinated inauthentic accounts.. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 18, pp. 164-176).

Bias in Data and AI Fairness

Our reliance on data to fuel AI raises important questions about fairness and ethics. Social data is often heterogeneous, as it comes from a population composed of subgroups with different characteristics and behaviors. A trend in aggregate data may disappear or reverse when the data is disaggregated into its constituent subgroups. This effect, known as Simpson's paradox, often confounds models learned from data. We are developing methods to quantify biases in heterogeneous data. One approach leverages the Simpson's paradox by accounting for latent groups to learn more robust and generalizable models. We are also developing principled mathematical methods to create unbiased features for learning fair models, or use affirmative action to improve collective outcomes of interventions.

Representative publications

- Mehrabi, N., Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K., & Galstyan, A. (2021). A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 54(6), 1-35.

- Lerman, K. (2018). Computational social scientist beware: Simpson's paradox in behavioral data. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1(1), 49-58.

- He, Y., Burghardt, K., & Lerman, K. (2020, February). A geometric solution to fair representations. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 279-285).

Gender Bias in Science

Despite long-term efforts to increase women’s representation in the scientific workforce, they continue to face barriers to advancement. We showed that women publish in less prestigious journals and receive fewer citations. The multifaceted gender disparities create a glass ceiling, an invisible barrier that fundamentally limits professional opportunities for even the best women scientists. The Covid-19 pandemic has only amplified existing gender disparities. To address these challenges, we are developing methods to audit gender biases in science. One recent example is a PNAS paper which identified gender disparities in the citations of members of the National Academy of Sciences. These differences, moreover, were strong enough to enable us to accurately predict the scholar’s gender from their citation networks. We have also developed a model of growing citation networks that explains the emergence of gender disparities in science.

Representative publications

- Lerman, K., Yu, Y., Morstatter, F., & Pujara, J. (2022). Gendered citation patterns among the scientific elite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(40), e2206070119.

- Nettasinghe, B., Alipourfard, N., Krishnamurthy, V., & Lerman, K. (2021). Emergence of structural inequalities in scientific citation networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.10944.

Friendship Paradox in Social Networks

Social networks shape perceptions by exposing people to the opinions of their peers. However, an individual’s perceived popularity of some trait or an opinion may be very different from its actual prevalence in the network. This perception bias arises due to the friendship paradox, which states that “your friends are more popular than you, on average.” Mind bogglingly, the stronger version of the friendship paradox is also true for the vast majority of people: “most of your friends are more popular than you.” As a result, it may seem to you that most of your friends are more successful, wealthier and have more accomplished children. They even have cuter pets! Strong friendship paradox leads to mind-bending phenomena, like the Majority Illusion, in which a rare trait can appear to be exceedingly popular within most social circles. This can bias perceptions of popularity online: we showed that some topics on Twitter appear to be several times more popular than they really are, i.e., many more people see their friends talking about it compared to how many people are actually talking about it. Explaining these paradoxes mathematically required us to define a new property of social networks -- transsortativity -- which measures the correlation of the popularity of a node’s neighbors. Friendship paradox explains why your friends seem to lead more exciting lives than you do. On the downside, it could fuel negative social comparisons that are detrimental to mental health and wellbeing.

Representative publications

- Alipourfard, N., Nettasinghe, B., Abeliuk, A., Krishnamurthy, V., & Lerman, K. (2020). Friendship paradox biases perceptions in directed networks. Nature communications, 11(1), 707.

- Lerman, K., Yan, X., & Wu, X. Z. (2016). The" majority illusion" in social networks. PloS one, 11(2), e0147617.

- Wu, X. Z., Percus, A. G., & Lerman, K. (2017). Neighbor-neighbor correlations explain measurement bias in networks. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 5576.

- Hodas, N., Kooti, F., & Lerman, K. (2013). Friendship paradox redux: Your friends are more interesting than you. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 225-233).

Cognitive Bias in Online Interactions

The many decisions people make about what to pay attention to online shape social interactions and the spread of information on social media. Due to the constraints of available time and cognitive resources, the ease of discovery strongly impacts how people allocate their attention to social media content. As a consequence, the position of information in an individual’s social feed determines whether it will be seen, and the likelihood that it will be shared with followers. Accounting for these cognitive limits explains puzzling empirical observations: (i) information generally fails to “go viral” (ii) highly connected people are less likely to re-share information due to their higher information load. In addition, we often observe “performance deterioration”, wherein performance quality declines over the course of an online session, demonstrating that “attention is a finite resource.” We are studying the interplay between human cognitive limits, content and network structure to better understand and predict online interactions.

Representative publications

- Lerman, K. (2016). Information is not a virus, and other consequences of human cognitive limits. Future Internet, 8(2), 21.

- Singer, P., Ferrara, E., Kooti, F., Strohmaier, M., & Lerman, K. (2016). Evidence of online performance deterioration in user sessions on Reddit. PloS one, 11(8), e0161636.

- Burghardt, K., Alsina, E. F., Girvan, M., Rand, W., & Lerman, K. (2017). The myopia of crowds: Cognitive load and collective evaluation of answers on Stack Exchange. PloS one, 12(3), e0173610.

- Ver Steeg, G., Ghosh, R., & Lerman, K. (2011). What stops social epidemics? In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 377-384).

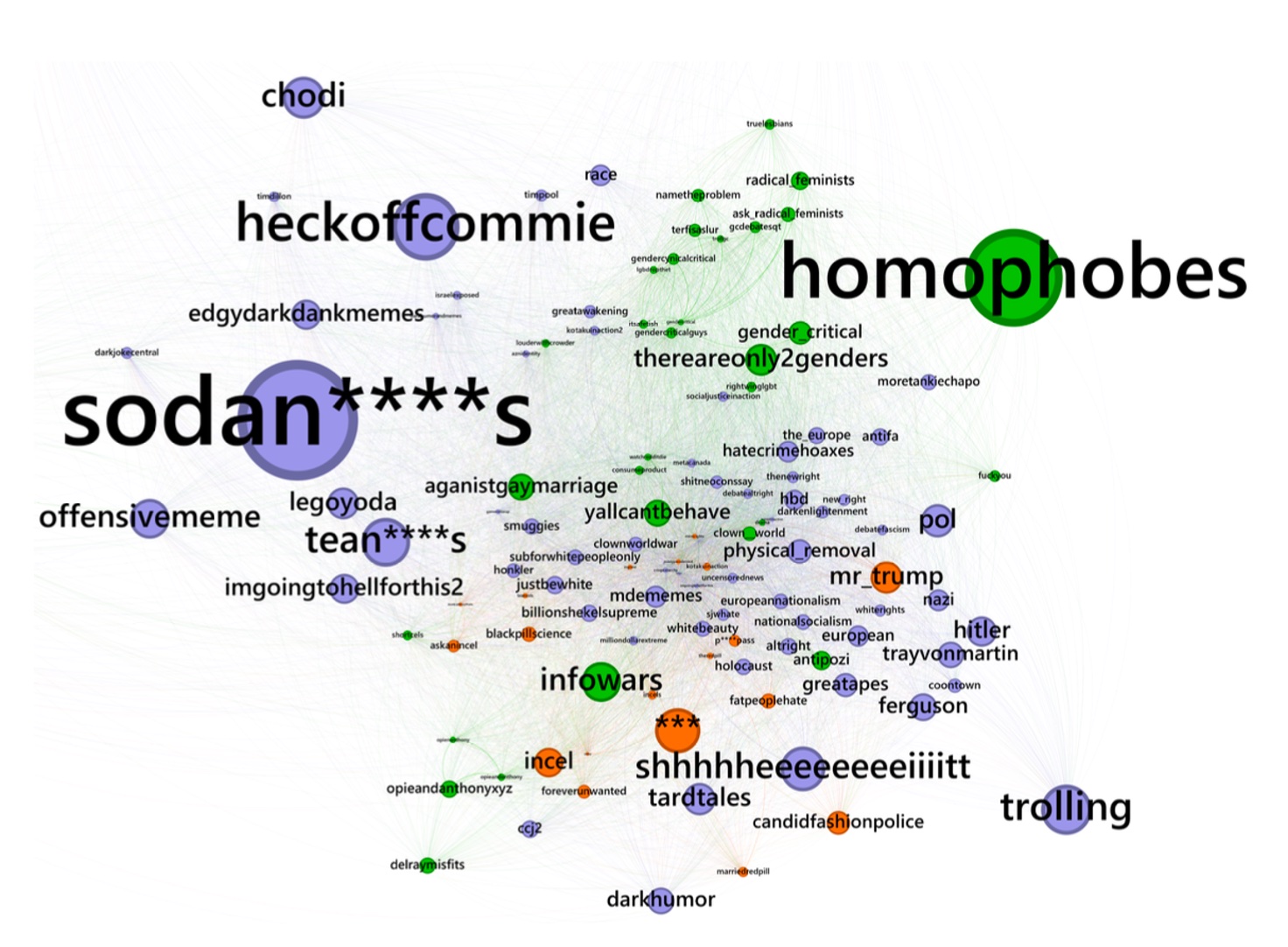

Social media-driven extremism

We develop novel AI models to understand and address extremism in social media platforms. Online groups are a direct cause for a substantial portion of offline hate crimes and are increasingly a primary driver of radicalization in the US. Our research aims to understand why people join these online groups and how these groups shape human behavior. More specifically, we utilize natural language processing, computer vision, recommender systems, and causal modeling techniques to analyze the lifecycle of extremism in online environments, from how people radicalize to how they leave. To understand this lifecycle, we have explored four complementary research questions: (1) What makes users susceptible to engaging in antisocial behavior, (2) What tactics are employed by harmful groups meant to influence users, (3)How do extremist online groups further radicalize users, and (4) How can users become deradicalized. This research adds to the nascent field of online extremist research with an emphasis on learning commonalities across different cultures and languages, whether Islamic extremism in Mozambique or hate groups in Europe. Applications of our research include new regulations to improve social media sites and automated techniques to deradicalize users who join extremist sites.

Representative publications

- Schmitz, M., Muric, G., Hickey, D., & Burghardt, K. (2024). Do users adopt extremist beliefs from exposure to hate subreddits? SNAM, 14(1), 1-12.

- Schmitz, M., Murić, G., & Burghardt, K. (2022). Quantifying How Hateful Communities Radicalize Online Users. In: ASONAM 2022, 139-146. IEEE. Runner-up Best Paper Award.

- Hickey, D., Schmitz, M., Fessler, D., Smaldino, P. E., Muric, G., & Burghardt, K. (2023). Auditing Elon Musk’s Impact on Hate Speech and Bots. In: ICWSM 2023, 17(1), 1133-1137. Reported on by the LA Times, The New York Times, Newsweek, CNBC, and others.

- Schmitz, M., Murić, G., & Burghardt, K. (2023). Detecting Anti-Vaccine Users on Twitter. In: ICWSM 2023, 17(1), 787-795.